A twelve-tone work of 1942 in 4 movements: Andante Molto allegro, Adagio & Giocoso. Schoenberg has given titles to each before retracting: “Life was so easy, “Suddenly animosity appears”, “A serious situation has arisen”, “But life goes on”.

So metaphysics settings – say sentimental – were pervasively present – but, above all, a quasi-romantic program could easily be adapted to serial music!

Created in 1944 by the NBC with Eduard Steuermann and Stokowski, this partition of about 20 minutes was recorded by (commercial recordings or pirates, according to Arnold Schönberg Center):

Claude Helffer / René Leibowitz (1952?)

Glenn Gloud / Jean-Marie Beaudet (1953),

Edward Steuermann / Hermann Scherchen (1954),

Alfred Brendel / Michael Gielen (1957),

Glenn Gould, Dimitri Mitropoulos (1958)

Glenn Gould / Robert Craft (1961)

Peter Serkin / Seiji Ozawa (1968),

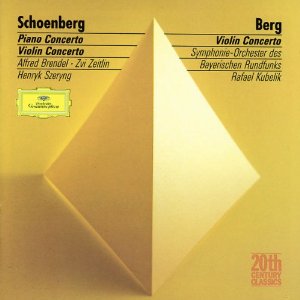

Alfred Brendel / Rafael Kubelik (1971),

Alfred Brendel / Bruno Maderna (1973),

Peter Serkin / Bruno Maderna (1973),

Adam Fellegi / Ivan Fischer (1979),

Peter Serkin / Pierre Boulez (1985),

Anatolii Vedernikov / Blazhkov Igor (1986),

Maurizio Pollini / Abbado (1988),

Theo Bruins / Chailly Riccardo (1989),

Emmanuel Ax / Esa-Pekka Salonen (1992),

Alfred Brendel / Michael Gielen (1993),

Amalie Malling / Michael Schonwandt (1994),

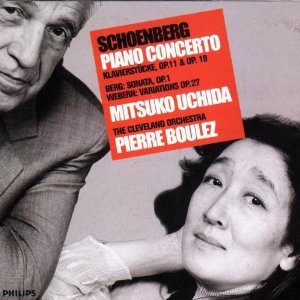

Mitsuko Ushida / Pierre Boulez (2000),

Christopher Oldfather / Robert Craft (2000).

To answer his critics who considered him as a cerebral composer, it is intriguing to see that, quoted in ‘Heart and brains’ written in 1946, he took the beginning of this concerto as an example of music coming from the heart, thus it is a serial music:

Versions compared here: Brendel / Kubelik (1971), Peter Serkin / Boulez (1985) and Uchida / Boulez (2000).

From the first movement, we leave aside the Serkin one: version very readable but nothing happens really there. The difference is staggering between both Brendel and Uchida and Kubelik and Boulez. The first play the Andante 4’45 instead of 4’28 for the second. Despite this relatively small difference, these 2 versions are completely opposite: the first a pianovery phrased, a superb atmosphere conform to the title given by Schoenberg, at the cost of little loose reading, then the second is very rhythmic, but in black and white.

The second movement shows the same differences, Brendel’s piano is more beautiful, reading Kubelík more ‘organic’ and colorful, but you may prefer the percussive piano Uchida here.

This time, the third movement is more rapid in Kubelík, yet with beautiful sounds and atmospheres, but here Boulez is more expressive, with a more structured speech.

The final movement, a rondo giocoso, sometimes curiously sounds like Prokofiev … As stated Misuko Ushida, the end sounds a bit hollow, like the finale of the Mahler 7th. Uchida / Boulez is on-going, with a suitable color. Brendel / Kubelík is quieter, perhaps with more marked dialogues piano / orchestra.

In conclusion, the amateur can choose between the more poetic version of Kubelík and the more decisive by Boulez. It will provide anyway in only 20’ at least as much music as in a Beethoven concerto… |