La boîte à joujoux – Claude Debussy / André Caplet [EN]

Continuer la lecture de La boîte à joujoux – Claude Debussy / André Caplet

Continuer la lecture de La boîte à joujoux – Claude Debussy / André Caplet

La boîte à joujoux – Claude Debussy / André Caplet [EN]

Continuer la lecture de La boîte à joujoux – Claude Debussy / André Caplet

Continuer la lecture de La boîte à joujoux – Claude Debussy / André Caplet

Zoltán Kodály – Sonate pour violoncelle seul – Cello sonata op. 8 – Emmanuelle Bertrand

|

La Sonate pour violoncelle op. 8 de Zoltán Kodály est devenue une pièce presque obligée du répertoire des violoncellistes ; on s’est amusé à recenser les versions plus ou moins disponibles…

En italique, celles que l’on a pu écouter. Il en manque (Piatigorsky…) et apparemment Rostropovitch ne l’a jamais enregistrée. Les versions Clein et Kliegel sont très honorables, Queyras (on se rappelle d’excellents concertos de Haydn et suites de Bach) est très élégant mais ça manque singulièrement de corps, Xavier Phillips n’a pas laissé grande impression. La seule version que l’on peut mettre en regard de celle d’E. Bertrand est celle du « prince des violoncellistes », Pierre Fournier, (ici dans un enregistrement public de 1959 (Praga) – à ce propos, on aimerait bien connaître celle du violoncelliste du quatuor Prazak, l’excellent Michael Kanka. Emmanuelle Bertrand prend son temps : 10 à 20% plus lente que Fournier dans chacun des 3 mouvements. On perd peut-être un peu de naturel dans les nombreuses figures rythmiques, mais on y gagne en intériorité : on se sent guider par elle dans un voyage intérieur, conforté par sa technique impeccable, son intonation infaillible, sa sonorité aussi aérienne que fruitée et la qualité exceptionnelle de la prise de son. Pour une fois, on est très content de toutes les distinctions qu’elle a pu recevoir récemment du milieu de la critique professionnelle. Une musicienne au sens fort du mot à la discographie déjà très fournie. |

The cello Sonata Op. 8 by Zoltán Kodály has become an almost obliged part of the repertory for cellists; we have listed –left– the versions more or less available… In italics, those we have listened to. Some surely are missing (Piatigorsky…) and apparently Rostropovitch never recorded it. The versions Clein and Kliegel are very honorable, Queyras (one remembers excellent concertos of Haydn and Bach Suites) is very elegant but presents a very light body, Xavier Philips did not leave great impression. The only version which one can place against E. Bertrand is from the “prince ofcellists”, Pierre Fournier, (here in a public recording of 1959 (Praga) – on this subject, we would like to listen to the version by the cellist of the Prazak quartet, the excellent Michael Kanka. Emmanuelle Bertrand takes her time: 10 to 20% slower than Fournier in each of the 3 movements. Perhaps we lose a little naturalness in the many rhythmic figures, but we gain in interiority: one feels to be guided in an interior voyage, consolidated by her impeccable technique, her infallible intonation, her splendid sonority and the exceptional quality of the sound recording. For once, we agree with all the distinctions she recently received from the (French) professional criticis. A true musician with an already extensive discography. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

L’album, à côté de la suite n° 3 de Britten et d’une suite de Gaspar Cassado, propose Itinérance, de son compagnon Pascal Amoyel, œuvre très prenante, plus immémorialle que contemporaine, qui se termine par le chant – vocal – de la violoncelliste, comme pour exprimer l’indicible de la condition humaine. Je n’en dirai pas plus que l’excellent commentaire de l’album dû à Sylviane Falcinelli. L’album est complété par un DVD intéressant, notamment une séquence de travail sur la sonate de Kodaly, la complicité de son directeur artistique lors de l’enregistrement et l’intervention de Pascal Amoyel (photo). Cf. aussi « Le concert idéal« . Un maître-disque ! |

Besides Britten Suite n° 3 and a Suite by Gaspar Cassado, the album proposes Itinérance, a work by her companion Pascal Amoyel, a very fascinating work, more unmemorable than contemporary, which ends with the singing – vocal – of the violoncellist, like telling the inexpressible human condition. I will not tell more than the excellent comment of the album by Sylviane Falcinelli [fr]. The album is supplemented by an interesting DVD, in particular a sequence on the Kodaly sonata, the complicity with her artistic director during the recording and the intervention of Pascal Amoyel (photo). Magnifiscent… |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Henri Dutilleux – 2e symphonie – 2nd symphony

|

L’aîné des compositeurs français vivants, âgé de 96 ans, Dutilleux aura été une des figures marquantes de la musique du XXe siècle. Pour aborder son œuvre, on peut certes commencer par la musique de ballet Le loup dont il existe un fameux enregistrement par Georges Prêtre, repris d’ailleurs dans un coffret économique de 5 CD chez Virgin, mais aussi par cette 2e symphonie « le Double » (1959). Le fameux couplage Tout un monde lointain avec ce concerto pour violoncelle de Lutoslawski par Rostropovitch montrait bien l’antagonisme de style entre les deux compositeurs : au dynamisme un peu rude du Polonais répondait l’élégance et le raffinement du Français. Pour Henri Dutilleux : « le processus de mémoire joue un grand rôle dans la plupart de mes partitions ». Effectivement, l’approche de la musique de Dutilleux nécessite un attention certaine, malgré un langage harmonique qui n’heurte pas. Une fois surmonté un certain hermétisme dû à la complexité de la construction et à une certaine uniformité apparente de ton, on se repaît ensuite des couleurs et des ambiances si poétiques de cette musique. L’ostracisme ambiant en France vis-à-vis des compositeurs qui n’étaient pas dans la ligne « Boulézienne » fit que Dutilleux dut se tourner vers l’étranger pour des commandes (Koussevitsky, Szell, Ozawa…). Il semble d’ailleurs que son jeune cadet Boulez n’ait jamais dirigé sa musique alors qu’il l’a fait il y quelques années pour André Jolivet, qu’il surnommait pourtant « joli navet » dans sa jeunesse. Néanmoins le « boulézien » Philippe Manoury déclarait dans un récent ouvrage considérer le quatuor Ainsi la nuit comme un chef d’œuvre absolu. On a comparé les versions Barenboïm, Bychkov et Tortelier (il existe par ailleurs Graf, Munch, Plasson et Saraste). Mentionnons que le titre Le double fait référence au fait qu’il y a deux ensembles instrumentaux qui se répondent : un groupe de 12 instruments (dont un clavecin) et l’orchestre. Mais c’est bien difficile à percevoir au disque. L’œuvre commence par un motif incantatoire qui fait irrésistiblement penser au Loup. Les trois mouvements seront une suite de variations, notamment sur ce motif. On a pu parler à propos de cette symphonie des influences croisées de Schoenberg (Dutilleux cite volontiers Farben des 5 pièces op. 16), Debussy ou Stravinsky. Si l’on entend effectivement certaines ambiances du Sacre dans le 3e mouvement, on pourrait aussi se référer au dernier Honegger, à Bartok, voire à Dukas… Des trois versions, bien que le compositeur a déclaré très apprécier celle de Tortelier, on a retenu plutôt Barenboïm pour le soin donné aux phrasés et aux couleurs, mais il nous semble que Bychkov y donne un peu plus de dynamisme. En outre, son disque se poursuit avec Timbres, espace, mouvement (1978) (mais on a l’impression d’entre la suite du Double…) et surtout les Métaboles (1964), œuvre phare du compositeur. |

The elder of French composers – 96 years old -Henri Dutilleux will have been one of the outstanding figures of the music of the XXth century. To approach his work, one can certainly begin with the ballet music Le loup – there is a famous recording by George Prêtre, included in an economic box of 5 CD at Virgin -, but also by this 2nd symphony “the Double” (1959). Once overcome a certain hermetism due to the complexity of construction and an apparent uniformity of tone, one goes back to the colors and so poetic environments of this music. Ambient ostracism in France with composers who were not in the “Boulezian” line made Dutilleux to turn to the foreign countries for commissioning (Koussevitsky, Szell, Ozawa…). It seems besides that Boulez never conducted his music whereas he did it a few years ago for André Jolivet, whom he called “pretty turnip (joli navet)” in his youth. Nevertheless, the “boulezian” Philippe Manoury stated in a recent book that Ainsi la nuit was an absolute chef d’œuvre. We have compared the Barenboïm, Bychkov and Tortelier versions (there is in addition Graf, Munch, Plasson and Saraste). Let us mention that the title Le double refers to the fact that there are two instrumental sets: a group of 12 instruments (including a harpsichord) and the orchester. But it is quite difficult to perceive it on a stereo set. Work starts with a “plaintive call” which irresistibly makes think of Le loup. The three movements will be a succession of variations, in particular on this motive. Influences have been quoted about this symphony: Schoenberg (Dutilleux quotes readily Farben of the 5 pieces Op. 16), Debussy or Stravinsky. If one hears indeed certain patternss of Le sacre in the 3rd movement, one could also refer to the last Honegger, Bartok, even Dukas… |

Falla – Nuits dans les jardins d’Espagne – Nights in the Gardens of Spain

|

Falla – Nuits dans les jardins d’Espagne – Nights in the Gardens of Spain |

|

Ne lisez pas tout de suite ce qui suit ! c’est une tentative de réhabiliter une fois de plus un enregistrement mésestimé de Kubelik. Mais ce n’est pas le plus important : l’important est que Pierre Barbier – Pragadigitals -a encore réussi un tour de magie : tout mélomane un peu âgé connaît par cœur cet enregistrement du Tricorne par Ansermet, non seulement par son indépassable interprétation, mais aussi par la « fabuleuse » prise de son Decca de l’époque. Eh bien, il réussit à nous restituer encore mieux cet enregistrement : les timbres sont mieux caractérisés, il y a « de l’air » entre les instruments, et surtout on « sent » le chef d’orchestre diriger, comme pour une bonne prise de concert, comme si on était dans le studio. On entend même pour la première fois une légère fausse note à 2’54 » dans le 2e mouvement du Tricorne… Bref, précipitez-vous ! Il est bien intéressant de pouvoir comparer deux versions des Nuits dans les jardins d’Espagne a priori bien différentes, voire antagonistes : d’un côté une pianiste très célèbre qui fut à ses dires quasiment toujours mécontente de ses enregistrements studio avec orchestre et dont un des chefs d’orchestre préférés était Raphaël Kubelík, de l’autre une pianiste, Margrit Weber, dont on sait peu de choses de nos jours, avec un chef alors vedette du fameux label jaune qui accepta d’enregistrer en studio des œuvres qui n’étaient pas à son répertoire habituel : Concerto de Grieg, Fireworks ou Water music de Haendel, etc. La version Kubelík est-elle si musicienne mais un peu Franckiste comme j’ai pu l’écrire ? 1er mouvement : Chez Kubelík, l’entrée est superbe, le piano moins brillant que l’on attendrait, un peu dans les touches de l’instrument. De l’abattage de la part de la pianiste mais çà ne sonne pas espagnol, plutôt un peu « gras ». Kubelík est là tel un grand maître, on le voit diriger cela… Avec Haskil / Markevitch, c’est plus posé, avec des sonorités plus recherchées, mais c’est moins « organique », l’orchestre est plus extraverti que chez Kubelík, mais il a tendance à couvrir la soliste, qui ne fait d’ailleurs pas forte impression. Bref, si l’orchestre fait (faussement ?) plus couleur locale, mais avec apparemment un accord de l’orchestre un peu plus haut, on est un peu mitigé. Le 2e mouvement : on se dit que c’est tellement espagnol (quel compositeur !) que Kubelík va avoir du mal, surtout vue l’imbrication piano / orchestre de ce mouvement ; le piano est toujours un peu en retrait au point de vue des timbres mais a de l’alacrité, certes les vents n’ont pas tout à fait la couleur idoine, le rythme peut paraître un poil empesé… mais tout est tellement musical. Haskil : c’est un peu plus rapide, encore un peu réglé plus haut, c’est plus criard et extraverti, mais on peut prendre çà comme une qualité ici, le pianisme est plus délié, mais on ne peut s’empêcher de penser que la caractérisation plus importante de la partition se fait au détriment de son unité : beaucoup de -superbes- effets à l’orchestre mais quand la pianiste veut être à l’unisson, çà détimbre un peu. On est encore moins sûr pour le 3e mouvement : c’es toujours apparemment plus vivant chez Markevitch, mais c’est quand même assez brouillon et un peu agressif au niveau de l’orchestre et le piano sonne dur. |

Do not read immediately what follows! It is an attempt to once more rehabilitate a low esteemed recording of Kubelik. But it is not the most important: the important thing is that Pierre Barbier – PragaDigitals – has again made a turn of magic: any rather old music lover knows this recording of the Three cornered hat by Ansermet, not only by his unsurpassed interpretation, but also by the “fabulous” sound recording Decca of 1961. Well, it’s even better in this reissue, restored from original tapes : tones are more characterized, there is “air” between the instruments, and one can feel the conductor’s gestures, as for a good live recording, as if one were in the studio. Just get it! It is quite interesting to be able to compare two versions of the Nights in the gardens of Spain a priori so different, even antagonistic: on a side a very famous pianist who declared being almost always dissatisfied with her studio recordings with orchestra, whom one of her preferred conductors was Raphaël Kubelík, on the other side, a pianist, Margrit Weber, with a conductor who accepted for the famous yellow label to record in studio works which didn’t belong to his usual repertory: Concerto of Grieg, Fireworks or Watermusic by Haendel, aso. 1st movement: With Kubelík, the entry is superb; the piano has less brilliance we could expect. Mastery from the pianist but it does not sound Spanish, rather a little “fatty”. Kubelík is there as usual a superb musician, one sees him directing that… 2nd movement: one thinks that it is so Spanish that Kubelík will not pass, especially with the overlap piano/orchestra of this movement; the piano is a little soft-toned, but has alacrity, certainly the winds do not have the suitable color, the rhythm can appear a little bit heavy… but all is so musical. We are even less sure for the 3rd movement: it is always apparently more alive with Markevitch, but it is nevertheless rather aggressive at the orchestra and the piano sounds hard. In short, more musicianship with Kubelík, but more “local colour” and alive with Markevitch. |

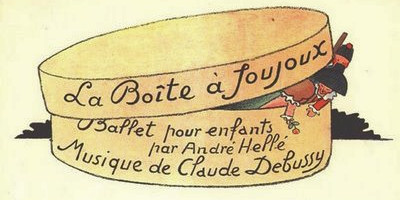

Arnold Schoenberg – 5 pieces op. 16 – Kubelik

Kubelik conducts Schoenberg Continuer la lecture de Arnold Schoenberg – 5 pieces op. 16 – Kubelik

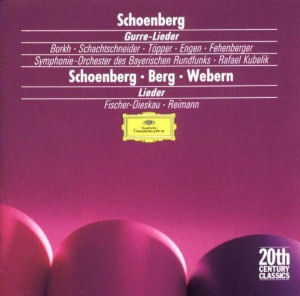

Schönberg Gurrelieder – Rafael Kubelík

Continuer la lecture de Schönberg Gurrelieder – Rafael Kubelík

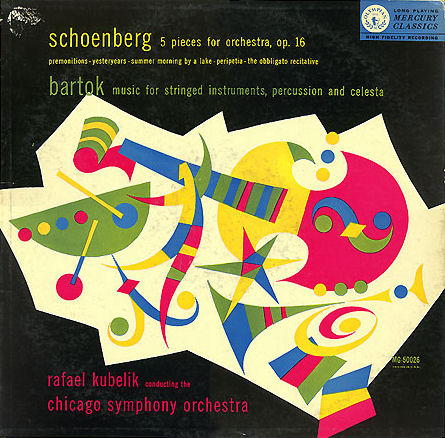

Arnold Schönberg – Pierrot lunaire – Alda Caiello – Prazák Quartet – Suite op.29