Jindrich Feld (1925-2007) – Praga

A propos des chefs alcooliques – On alcoholic conductors

Continuer la lecture de A propos des chefs alcooliques – On alcoholic conductors

François Sarhan – Interview

Continuer la lecture de François Sarhan : Une nouvelle génération de compositeur – A new generation of composer

Philippe Manoury – Gesänge-Gedanken mit Friedrich Nietzsche – Introduction

Continuer la lecture de Philippe Manoury – Gesänge-Gedanken mit Friedrich Nietzsche – Introduction

Emmanuelle Bertrand – Pascal Amoyel – Chostakovitch

Emmanuelle Bertrand – Pascal Amoyel – Chostakovitch Continuer la lecture de Emmanuelle Bertrand – Pascal Amoyel – Chostakovitch

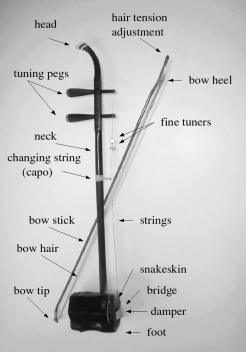

Erhu – Morin khuur : 1000 ans – Violon / violin : 600 ans

Continuer la lecture de Erhu – Morin khuur : 1000 ans – Violon / violin : 600 ans